Genealogist Amy Johnson Crow, who blogs at No Story Too Small, has set a challenge to write about one ancestor each week. I’ve decided to take up that challenge to wake up my (somewhat) languishing blog, but to honor my ancestors. I plan to post every week on Sunday, and I encourage others to join the challenge with me.

Genealogist Amy Johnson Crow, who blogs at No Story Too Small, has set a challenge to write about one ancestor each week. I’ve decided to take up that challenge to wake up my (somewhat) languishing blog, but to honor my ancestors. I plan to post every week on Sunday, and I encourage others to join the challenge with me.

Private, Company B, 161st Regiment, New York Volunteers

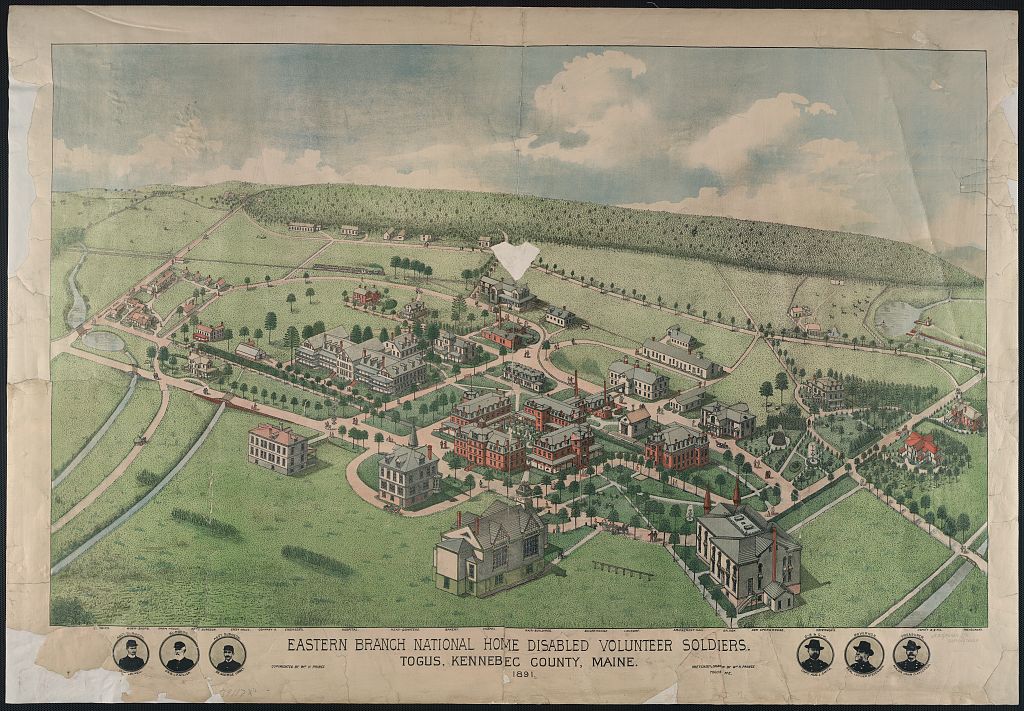

Rheumatism, disease of heart, liver, stomach and lungs, catarrh and varicose veins. That was the description of Charles Lattin’s disability on his Civil War pension document. He had joined Company B of the 161st Regiment, New York Volunteers in August of 1862 when he was 18 years old. Nearly 40 years later, he was in poor health and living at the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Togus, Kennebec County, Maine. Where was his wife and family?

National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Togus, Kennebec County, Maine. 1891. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Charles Lattin (1843 – 1917) was my great-great uncle, married to Sophia Ophelia Roberts. He was born in New York in Watkins, Schuyler County, and according to his Civil War service records, married Sophia in nearby Chemung County. From what I could find about the two of them, they both endured difficult times.

No census records have yet been found that show Charles and Sophia together with any of their four children. Oddly, they are missing in 1870 and 1880, the only two U.S. censuses where they should be together as husband and wife. I haven’t found them in the 1875 New York State census either. Charles was a boatman on the Erie Canal; one possibility is that the family was on the water during census-taking, and did not get enumerated.

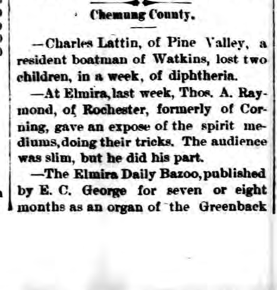

Sadly, records from the Pine Valley Cemetery in Catlin, New York, along with a newspaper account, reveal that Charles and Sophia lost 3 children within a span of 4 days in April 1878—the youngest was 2 months old; the oldest 4 years. Two died of diphtheria and I would presume the third did as well. They died between U.S. census years, and without newspaper or cemetery records, their existence would have been difficult to discover.

Three years after Charles lost his three children, his wife died. Other than an unnamed (and still unknown) 12-year-old daughter mentioned in the obituary, he was all alone. The first record he shows up in after his wife’s death in 1881 is the 1897 entry in the list of residents in the soldier’s home in Maine. Three years later, he had moved closer to his home town and was living in the New York State Soldiers and Sailors Home in Bath, Steuben County, New York.

New York State Soldiers and Sailors Home, Bath, New York. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

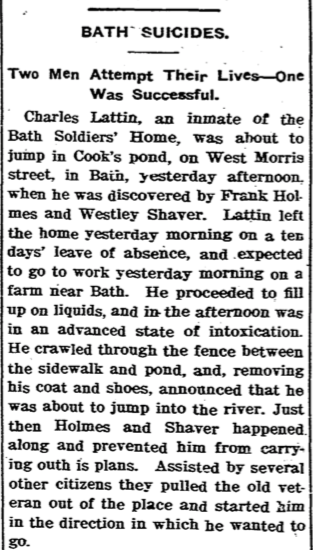

But it all appears have been too much for him, as Charles was reported to have attempted suicide. The 1901 Hornellsville Evening Tribune headlines stated: Two Men Attempt Their Lives—One Was Successful.

Charles continued living at the home for another 16 years until his death on December 11, 1917 when he was 74 years old, and he was buried at the Bath National Cemetery. Perhaps it was due to his “advanced state of intoxication” and not a deliberate attempt to end his life that led Charles to the lake. I would like to think so. But my heart goes out to him. To lose three children and a young wife in a short span of time would try anyone’s soul.

Pingback: 52 Ancestors Challenge: Week 11 Recap | No Story Too Small